064 – China Granite Project I

064 – China Granite Project I

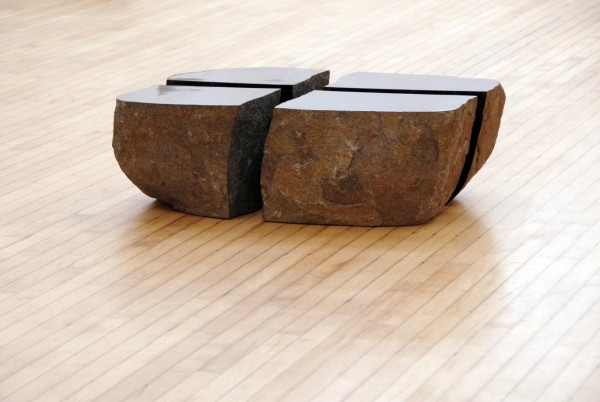

China Granite Project I

2009

An Li Stone Company, Chengnanzhuang, Hebei Province, China

Various dimensions

Produced for Johnson Trading Gallery

The name Granite comes from the Latin word granum, meaning grain, and is an igneous rock formed of highly compacted crystalline grains created during the solidification of magma. Granite can vary in colour from whites, pinks, blues and greens through to dense black depending upon localised geochemistry and mineralogy. From just one quarry in Pai Fang Village I collected boulders of both emerald green and jet-black granite with which to produce my China Granite Project.

I worked in close collaboration with a small stone yard called An Li Stone in Chengnanzhuang, Hebei Province, 350km southwest of Beijing. I don’t speak a word of Mandarin and the stone-yard workers not a word of English, but with the help of the young nephew of Ling Hejun, the owner of An Li Stone, who could speak a tiny bit of English (and the dictionary on his mobile phone), plenty of sign-language and sketches directly on the surface of each boulder, we were able to successfully realise a collection of furniture pieces in Chinese granite. These include a concave-cut boulder chair in Chinese green granite using the natural radius of the diamond blade, three straight-cut boulder chairs in both Chinese green granite and black granite, a natural split quarter table, a twin boulder table and a selection of boulder stools and tables. Each granite boulder was selected for it’s natural characteristics as generated through millions of years of geothermal activity and revealed during the quarrying process, and only the minimum amount of cutting was performed on each boulder to achieve the desired appearance and function. Each cut surface was then polished using graded diamond pads and water.

The first day was spent in An Li’s local granite quarry in nearby Pai Fang Village, where I was able to search the quarry freely for suitable pieces of granite. I didn’t know what I was looking for and of course it was impossible to know what to expect, but what I found was a vast embankment of irregular shaped but perfectly rounded boulders that had been pushed over the peak from the quarry on the other side of the mountain. This mass of quarry stones, too small for use as dimension stone, is generally ignored by the stone-yards who require large squared blocks of granite with consistent grain and structure. I searched through the pile of stones leveraging them out of the way with a steel bar to reach the boulders below and eventually accumulated a pile of almost 20 granite boulders. I didn’t plan to use all of them, but granite being a natural material, I knew that once cut some of the boulders would reveal cracks or imperfections that could render them useless. Once free from the mass I had a less distracted view of each individual stone and was able to reduce my selection. The smaller boulders were lifted onto a small three-wheeled truck (a cross between a Reliant Robin and a trailer) and the larger boulders loaded onto a powerful diesel flatbed truck, then transported across five miles of dusty pit-holed tracks to An Li stone yard in Chengnanzhuang.

I sketched onto the surface of each boulder with wax crayon, responding to the natural contours and inherent characteristics of each stone. Some of the stones were immediately rejected due to awkwardly positioned cracks or fissures, although I found one boulder with a natural seam perfectly in the centre that could be split by hammer and chisel into two halves. This particular stone later became a set of quarter tables by cutting through the granite adjacent to the natural seam. Every piece of granite, unique to its own, suggested a different application of cuts to give function to an otherwise redundant boulder.

Guidelines drawn, each boulder in turn was lifted onto the saw platform using a combination of rubber straps with a steel bar, apparently reclaimed and improvised from old engines, or the larger boulders with steel cable and the overhead beam winch. Once in place on the wooden platform we battled to manoeuvre each stone so that my wax lines were in a vertical plane parallel with the circular saw blade. Steel pegs were driven into the wooden beams around the edge of the boulder to hold it in place and wooden wedges were tapped underneath to prevent wobbling during the fierce cutting process. The entire saw platform was then rolled along the railway tracks into the brick building and locked in place once aligned with the 2.5 metre diameter diamond saw blade. Following the wax lines on each boulder the saw operator, in this case the lady who also cooked breakfast, lunch and dinner for the entire stone-yard, myself included, would turn on the water and begin cutting through the granite. The blade was slowly moved forwards into the stone cutting through approximately one inch of granite and once clear through the opposite side the blade was lowered another inch and traversed back through the stone. This process continued until the correct depth had been cut. For each additional cut parallel to the first the saw table simply had to be rolled along the rails to the desired distance and then locked in place. But for subsequent cuts on a different plane or at a different angle the saw table had to be rolled out of the building and the boulder totally repositioned until once again the crayon lines were aligned parallel to the saw blade. Without a single flat surface or square edge on any of the boulders the process of accurately aligning a half tonne granite boulder to make two adjacent cuts at a specific angle greater than 90 degrees is a nigh on impossible task. We measured and measured again, then cut once.

To give contrast to the naturally rough exterior of the boulders and to reveal the inherent crystalline structure of the granite I made the early decision to polish each of the cut surfaces. Due to the incredible hardness of granite the polishing process is stubbornly slow, beginning with grinding the surface flat and then using rotary diamond sanding discs and water. To put the process into perspective marble begins to achieve a polish at 600 grit whereas granite doesn’t achieve a polish until 3000 grit. Once polished the surface of the granite achieves a mirror-like quality and the true colour and grain of the minerals within the stone is revealed. The result is worth all the effort, but the exterior surface of the granite, as created by the forces of nature, is every bit as beautiful as the inside.

My project with Pai Fang quarry and An Li Stone resulted in a mutual exchange of discovery, laughter and smiles, and a collection of 19 furniture pieces. They are to be seen as boulders of natural granite, and used as furniture.

China Granite Project materialised during a two-week residency programme organised by the Chinese International Gallery Exposition (CIGE) and Alexander von Vegesack of the Vitra Design Museum, to nurture an artistic response to Chinese culture and industry.